““[Partisanship] serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection... [Parties] are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people, and to usurp for themselves the reins of government; destroying afterwards the very engines, which have lifted them to unjust dominion.””

Ingroups.

Political party affiliation often serves as a marker for a particular set of beliefs about the role of government in our lives or particular policy preferences. However, party affiliation has also become an increasingly important identity for people in recent years. Rather than signaling a particular set of beliefs about the role of government in our lives or about particular policy preferences, party affiliation provides a social signal for whether a person is “one of us” (in the ingroup) or “one of them” (in the outgroup). Ingroup favoritism (or bias) is a well-documented phenomena wherein people give preferential treatment to a group they belong to.

What happens when policy beliefs and ingroup favoritism conflict?

For this study, I examined what happens to policy support when a typical Republican policy view — affirmative action programs should not exist — against a situation in which an affirmative action program would benefit Republicans. I then took it one step further, examining how including the term “affirmative action” in the description of the policy might change levels of support.

clear ingroup favoritism

I sent surveys to self-identified Republicans, starting them off with the following hypothetical:

“Research has shown that Republicans [Democrats] are not well represented in certain areas of academia.

Would you support a[n] [Affirmative Action] program that requires universities to ensure that a specific percentage of its faculty and staff are Republicans [Democrats]?”

I varied whether the program benefitted Republicans or Democrats and whether I referred to it as an “Affirmative Action” program. Participants rated their support on a 7-point scale from 1 - Strongly Against to 7 - Strongly in Favor of (with Neither for nor against in the middle.)

Unsurprisingly, Republicans overwhelmingly reject this policy when it benefits Democrats, with ~85% against (see Figure 1.) This matches pretty closely with results from Pew Research finding that 75% of Republicans were against colleges considering race and ethnicity in admissions decisions. However, when it benefits them, a rift appears. A slight majority holds fast to Republican policy views on Affirmative Action, but over 1-in-3 now support the program. You can also see a jump in overall uncertainty relative to when the target is Democrats — more Republicans find themselves unsure of whether to be for or against the program when it benefits them.

Figure 1. The original scale is 1 to 7, but for the sake of simplicity, I’m just plotting Against, Neither, and In favor here. Also, these percents combine participants who did and did not have the program described as “Affirmative Action”.

maybe republicans simply aren’t taking the hypothetical seriously?

I can imagine the rebuttal to my interpretation here is that university faculties do, in fact, tend to be disproportionately Democratic-leaning. Perhaps the Republicans in this sample know this and are responding based on this knowledge (thus rejecting my premise.)

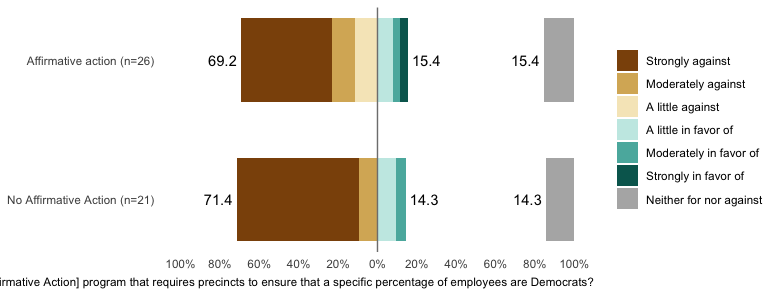

To account for this possibility, I ran a small survey (N = 47) that used a hypothetical in which Republicans actually tend to be more represented than Democrats — law enforcement. As you can see below, the pattern of results is unchanged when the hypothetical matches reality — Republicans don’t want preferential treatment for Democrats.

Figure 2.

Retrieval cues matter.

Next, let’s take a look at whether including Affirmative Action in the description of this policy matters. My hypothesis is describing the policy as “Affirmative Action” should reduce support for the program. I’m betting most of you have the same intuition. The reason for this hypothesis boils down to retrieval cues.

Attitudes (“I like this or I don’t like that”) are shaped by knowledge, values and beliefs. Which values are retrieved often depends on the retrieval cues at hand. Mentioning that Republicans are underrepresented in education may cue values of fairness and negative beliefs about liberalism and its effect on young minds. For some, mentioning a program meant to balance political representation will therefore yield positive attitudes. However, if we describe it as “Affirmative Action”, this will cue all sorts of other values and beliefs — namely, valuing freedom from government interference, and the belief that identity should not play a role in hiring decisions, and perhaps, most importantly in these days of negative partisanship — “a policy Democrats support“.

(Of course, even without calling it Affirmative Action, the description of the program will be enough for others to recognize that this sounds an awful lot like an Affirmative Action program.)

Therefore, when Affirmative Action is mentioned, whatever motivation for ingroup favoritism might exist will have to contend with the hypocrisy of supporting a policy that is popular among Democrats.

the “undecideds” turn the tide

Looking to the data, my general hypothesis was supported — mean support for this program is lower when it is described as an “Affirmative Action” program (3.25 out of 7) than when the term isn’t included (3.8 out of 7).

However, what I found really interesting, is that when you break it down by the percentage who chose each option, you see no real difference in terms of the percentage of Republicans who are in favor of the program! A little over 1/3 of Republicans support this regardless of whether or not it is called Affirmative Action. What we do see is that when it is not called Affirmative Action, a full 1/4 of Republicans are “Neither for nor against”. When it is called Affirmative Action, that goes down to a little over 1-in-10 and the % against jumps from 38% to 52%!

Figure 3. Reminder: the only difference between conditions is the words “Affirmative action” were either included or left out of the description — everything else was the same.

For the stats nerds — I ran a Bayesian ordinal regression with a cumulative link function — the effect of leaving out Affirmative action was b = 0.5 (probability of direction = 97.42%)

What I think is going on.

This was one of those studies where the hypothesis regarding the direction of the effect was fairly straightforward (i.e., average support goes down when Affirmative Action is mentioned), but by digging into the ordinal patterns (e.g., which % chose which option), we learned something interesting!

I think that most respondents in this study were likely dealing with an uncomfortable mix of competing motivations. This policy would clearly benefit Republicans. However, even when the program is not described as Affirmative Action, I would bet that most folks at least got the feeling that it sounded awfully familiar in an uncomfortable way.

Folks who were against could have simply recognized that the program sounds like Affirmative Action outright, leading them to feel uncomfortable with the hypocrisy of supporting Affirmative Action for themselves and opposing it otherwise. Another possibility is that the description itself cued enough values that disagree in principle with the program. Of course, when the program was described as Affirmative Action, this would only make these kind of folks more likely to oppose.

Those who were neither for nor against when Affirmative Action wasn’t mentioned likely felt the same tension I described above. It could be that they were less likely (than the “against” group) to consciously pin why they felt uncomfortable while also feeling the pressure of the ingroup. Therefore, rather than settle the dissonance between ingroup favoritism and an unconscious negative feeling towards the program, one can just sit on the fence. When the program is clearly described as Affirmative Action, it gives a name to that unconscious negative feeling, putting a thumb on the scale for opposition to the program.

Interestingly, support for the program was stable regardless of whether Affirmative Action was mentioned. These folks appear to prioritize benefits to the ingroup above all else. There could be some who see no issue with supporting it, because they aren’t familiar with Affirmative Action and they have a weak grasp of traditional policy stances. Still others may recognize the potential hypocrisy at play and decide that it doesn’t matter as long as the policy benefits their group (no doubt finding a justification that reframes the issue to make this position seem like the right one.)

Why this matters.

I think it is significant that the addition of just 2 words that provide no new information about a policy can move support by ~14 percentage points (37% against to 52% against.) It really drives home the importance of paying attention to how polling questions are worded (and I would argue, the importance of varying how the same questions are asked.) Our values, and beliefs are stored in memory and therefore are subject to the same rules as other memory traces. Variations on how a question is asked can elicit retrieval of different values and beliefs, setting us on one of many possible trains of thought.

Like the article? Consider supporting for more like it!

Click here to check out my Patreon page!

Survey details:

All surveys were posted on Cloud research. Participants were limited to those who selected Republican as party affilation.

Survey 1: “Imagine that a report was released that showed that Republicans are not well represented in certain areas of academia.“

No affirmative action condition: N = 106

Affirmative action condition: N = 94

Total N = 200

Mean age = 43 (sd = 12.26, min = 20, max = 80)

53% male, 46.5% female, 0.5% non-binary

Survey 2: “Imagine that a report was released that showed that Democrats are not well represented in certain areas of law enforcement…“

No affirmative action condition: N = 21

Affirmative action condition: N = 26

Total N = 47*

Mean age = 43 (sd = 16.05, min = 19, max = 99)

55.3% male, 42.6% female, 2.1% no answer

*I only collected 47 because this was not meant to examine the affirmative action vs. no affirmative action wording — it was just meant to show the very clear ingroup bias. (See below for a figure showing no real difference when Democrats are the target.)